Spanish Civil War memories have always been contentious. They have moved through a series of phases which can be chronologically related to the immediate post-war era, to the second half of the dictatorship, to the transition to democracy, and to the post-millennial period. These temporal shifts are also evident in the changing subjects, modes, and media of commemoration: the spaces and places of memory, the remembered and forgotten dead, memories of repression, the means of private and public transmission of memories within Spain, exile memories, and transnational commemorations of the War.

The exhibits in this section address these changing nature of these aspects of Spain’s Civil War memories since the late 1930s. Discussions of altered street names and memorials to the fallen of the war remind us of the importance of the inscription of memory in the landscapes, cities, and towns not only where battles or major events occurred, but also in daily life at national and community level. Attention to those individuals whose deaths are remembered or forgotten, and to the fate of victims whose stories have been elided from collective and cultural memory, tells us much about political and social exclusion following conflict. But the survival, private transmission and public vindication of the memories of those victims is also a story of memory’s capacity to demand redress for historical crimes and atrocities.

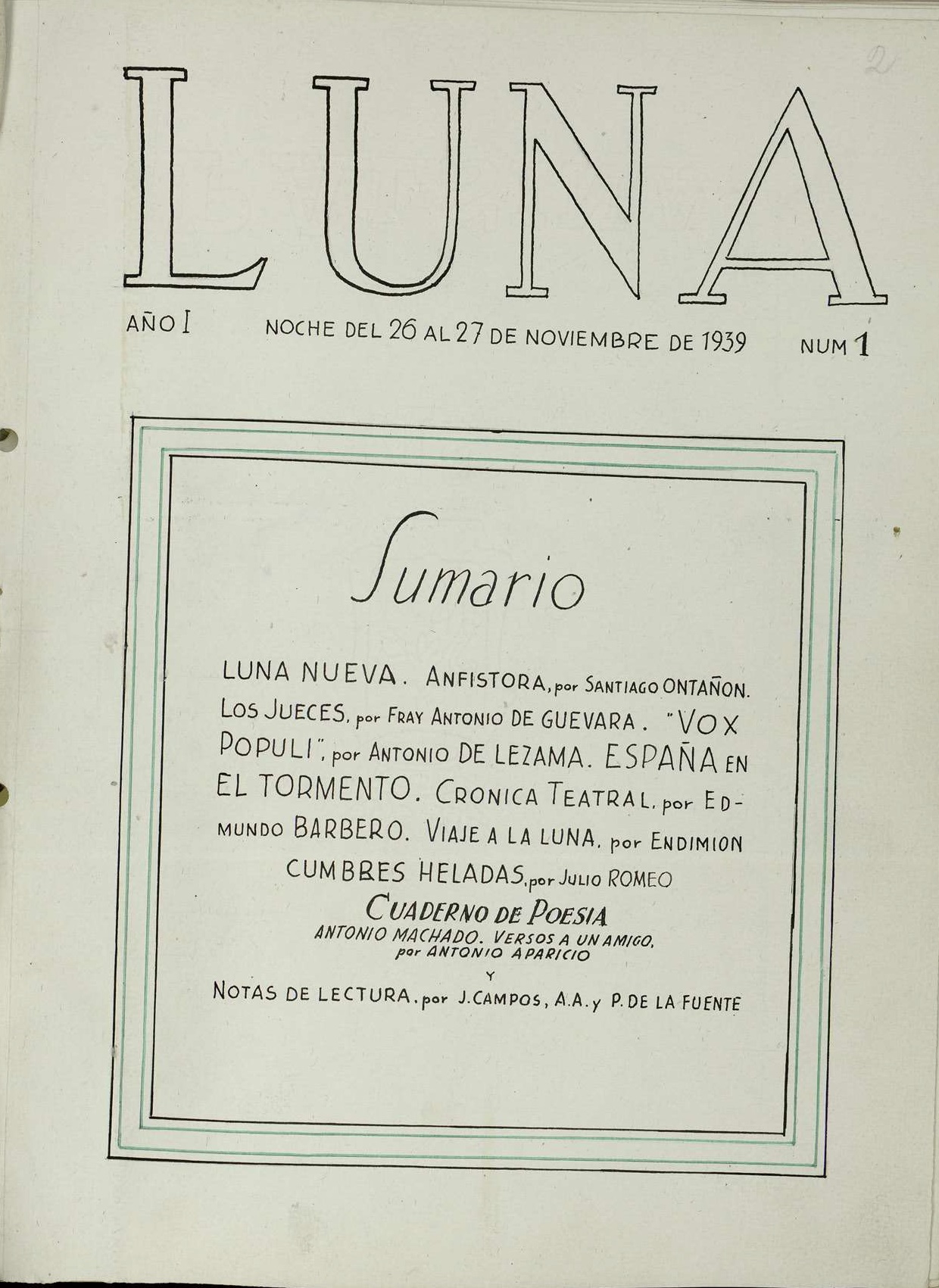

In the immediate post-war period, Nationalist memorial initiatives reinforced Franco’s victory and disqualified the vanquished from a presence in the national memorial horizon. This approach softened slightly, thought it did not substantially alter, in the second half of the dictatorship. As a result, while the Valley of the Fallen, initially planned to glorify only the Nationalist dead, may contain the fallen of both sides, this has never been seen as a neutral monument and remains the focus of a justified polemic.

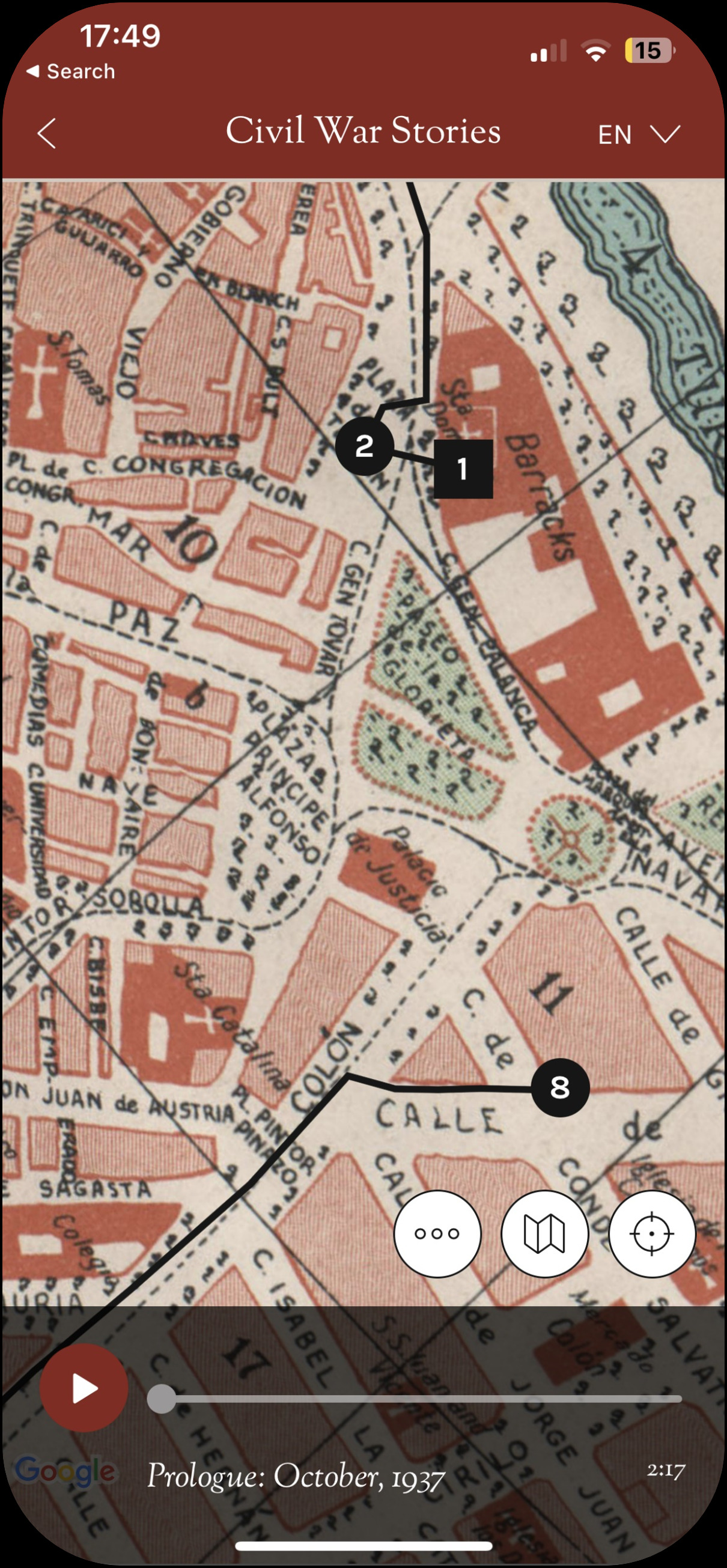

During the transition to democracy, Civil War memory was a latent lesson teaching consensus in the political domain, as Juan Carlos’ inauguration of an understated memorial to the Fallen of Spain illustrates, but this did not prevent new historical research on the war nor local and community initiatives proposing new subjects of memory, including through the changing of street names or some early exhumations of war-era mass graves.

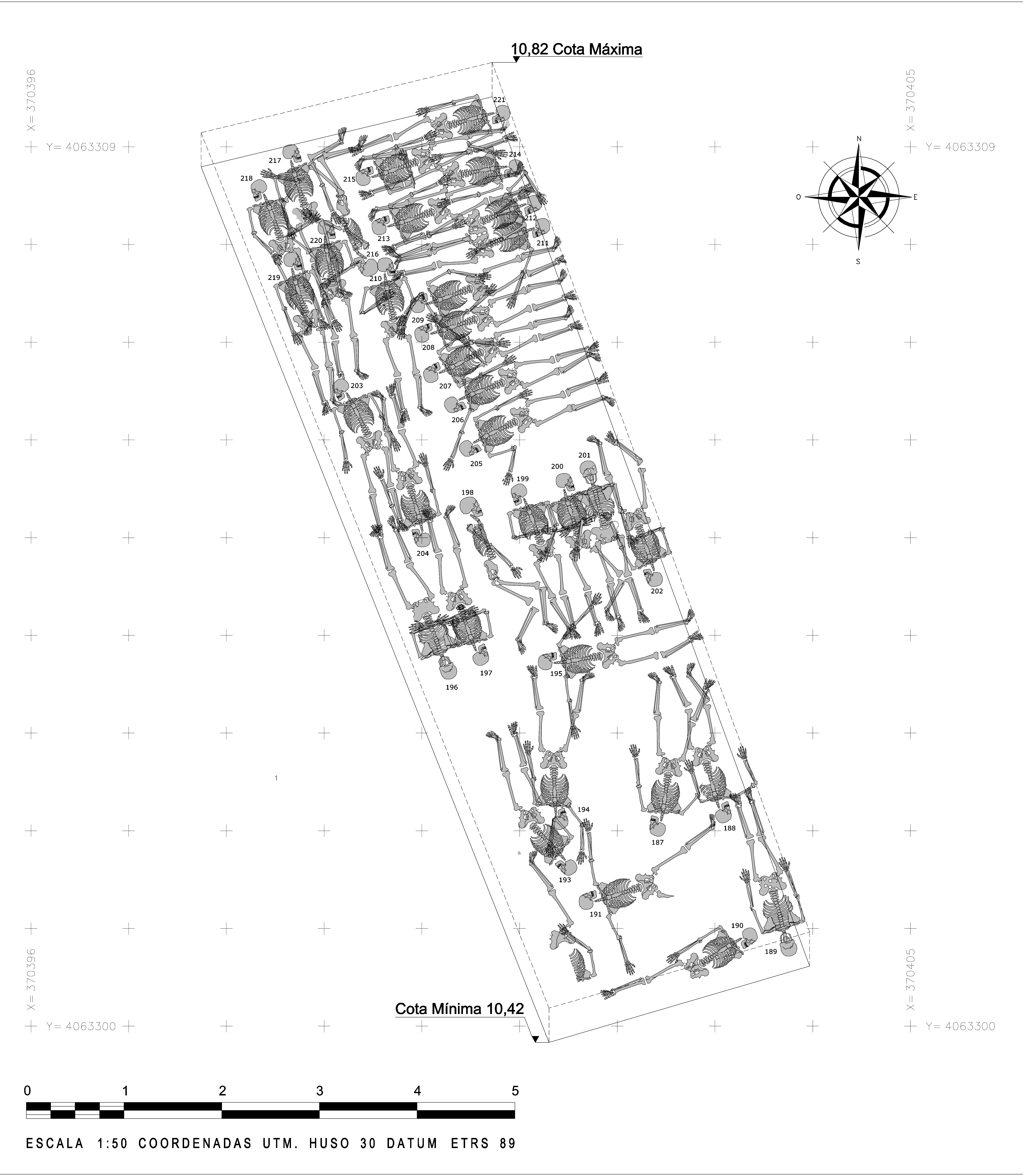

Around the turn of the millennium, a new impetus to redress the gaps in public memory shifted attention to those whose lives, deaths and suffering during the war and immediate post-war period had been silenced. In particular, we have seen the recovery and dignification of the remains of some of the victims of the Francoist repression, lying in mass graves or roadside pits since the time of the conflict, though too many locations still remain to be excavated. The experiences of the maquis who continued the struggle after the end of World War II, of women during and after the war, of exiles such as the Basque children sent to the UK during the war and not all of whom returned, are also now remembered in cultural productions and through the establishment of special archives. Finally, the war is an event of international significance which is commemorated round the world.