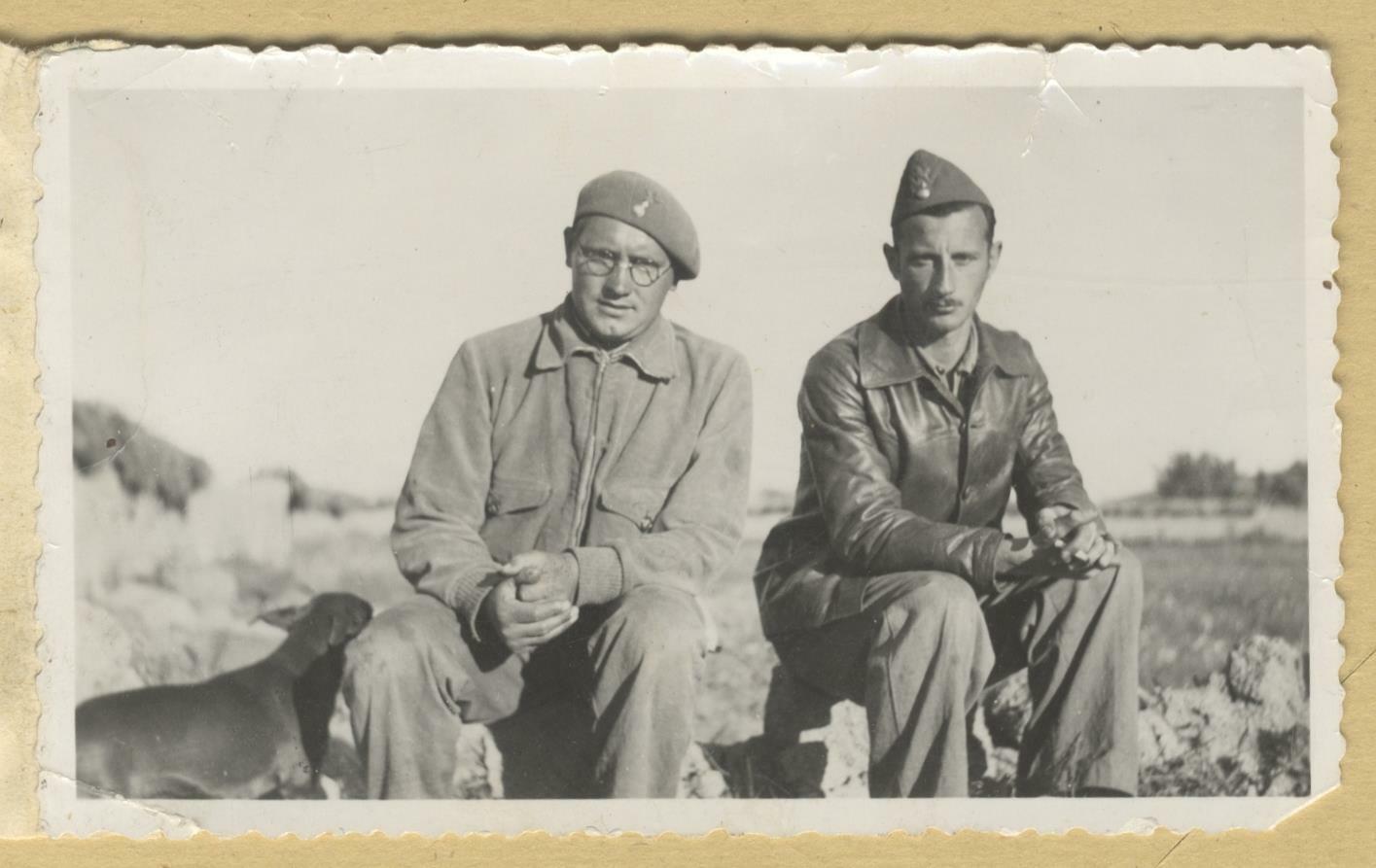

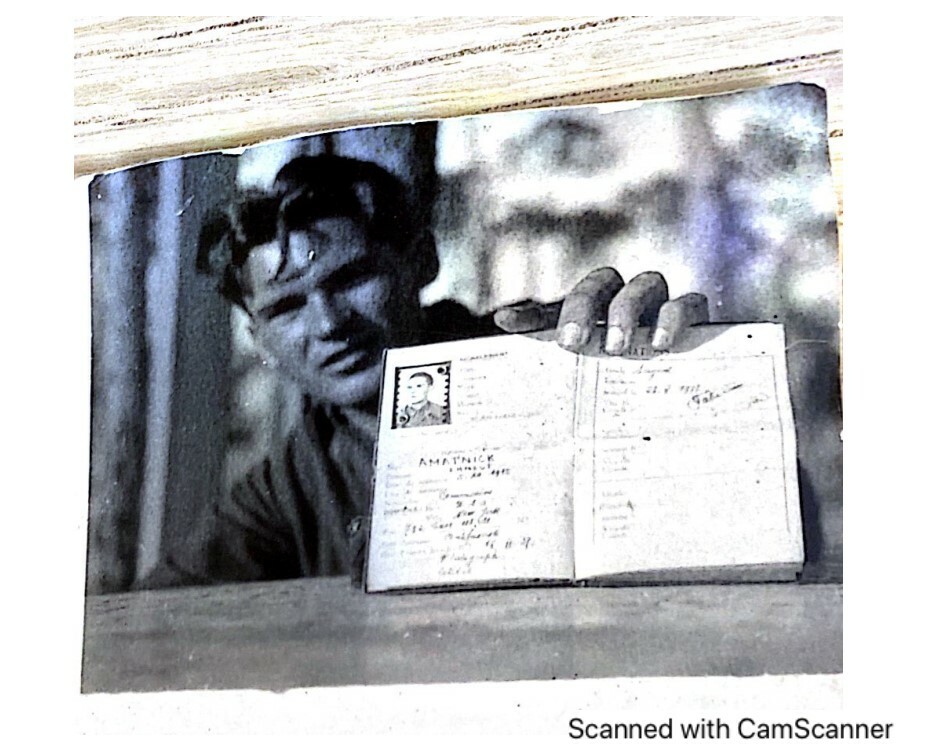

In August 1936, the Latvian government agreed to implement the Non-intervention policy and during the conflict it applied the prohibitions and guidelines adopted by the Non-Intervention Committee. Accordingly, after 23 February 1937, the recruitment of Latvian volunteers and participation in the conflict was prohibited. At first, employees of the Latvian Foreign Service and other high-ranking officials believed that violations of the Non-intervention policy were not relevant to Latvia. However, more than 80 volunteers from Latvia traveled to Spain to aid the Republic. Only one Latvian citizen is known to have served on Franco’s side. Furthermore, Latvian state institutions sold old stocks of war materiel to an intermediary who was involved in arms sales to Spain. As well as Latvian companies engaged in foreign arms transactions that were destined to Spain.

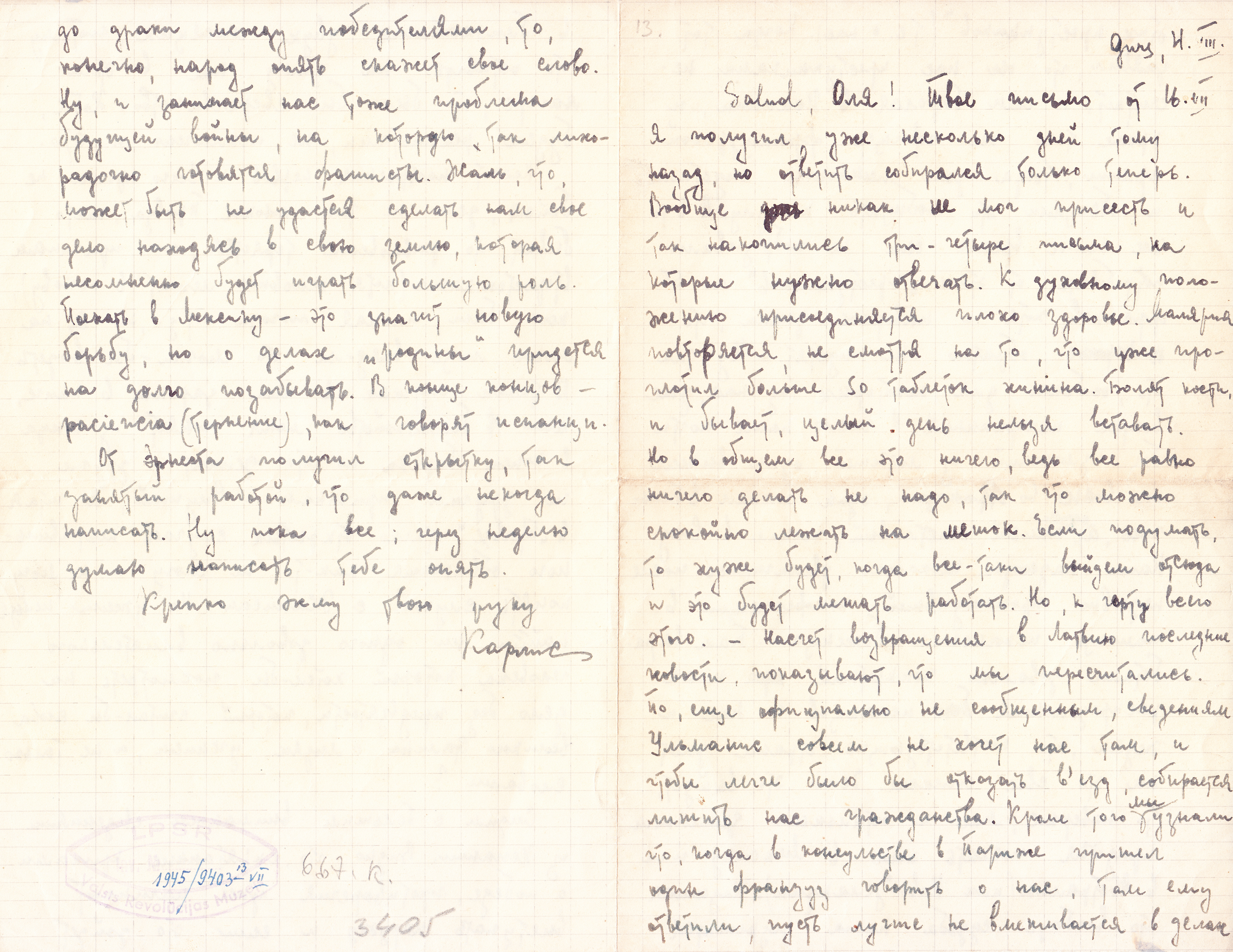

At the time, Latvia was governed by Kārlis Ulmanis, whose authoritarian dictatorship, established on 15 May 1934, was relatively mild. The regime was based on nationalism; however, it did not support any radicalism. Political parties were prohibited, and the media was controlled by the regime. Latvian society initially received conflicting information on situation in Spain. From Autumn 1936 until late 1937, the narrative in the largest Latvian newspapers was predominantly in favor of the rebels. They even published rebel propaganda. More objective information was available starting from 1938, when the new Press Law, prohibiting printing of unverified news unfavorable to Latvian diplomatic relations, entered into force.

Despite the activities of Latvian authorities, an illegal Communist press was created and distributed in small quantities. It supported the position of the USSR in the conflict, and the underground Latvian Communist Party, heavily influenced by the neighboring USSR, had a significant importance in recruitment of Latvian volunteers and collecting donations to the Spanish Republic.

During the Latvian SSR (1944-1990), the first recollections written by Latvians on the Republican side were published after the condemnation of Joseph Stalin's cult of personality. However, they were highly fragmented as censorship did not allow anything to be written about disciplinary violations by Latvians and any bad habits that volunteers had. Furthermore, Latvian experience could not include topics that discredited the USSR and many volunteers, who never came to the USSR, had to be erased from Soviet history. Only nowadays is the topic gaining renewed and more objective interest.

GIB