The conspiracy to overthrow the government began with a show of impotence. In the four provinces of Galicia, the elections of February 1936 produced broad support for the Republic. The centre-left Popular Front electoral coalition triumphed, especially in A Coruña and Pontevedra while centrist and conservative options lost and did well only in Lugo and Orense respectively. The openly anti-republican parties were completely marginalized. Galicia did not have a “tragic spring” as the authorities easily disrupted the attempts by the few Falangists in the region to destabilize things. On the contrary, the spring was a festival that culminated on 28 June with the vote on the Galicia Autonomy Statute.

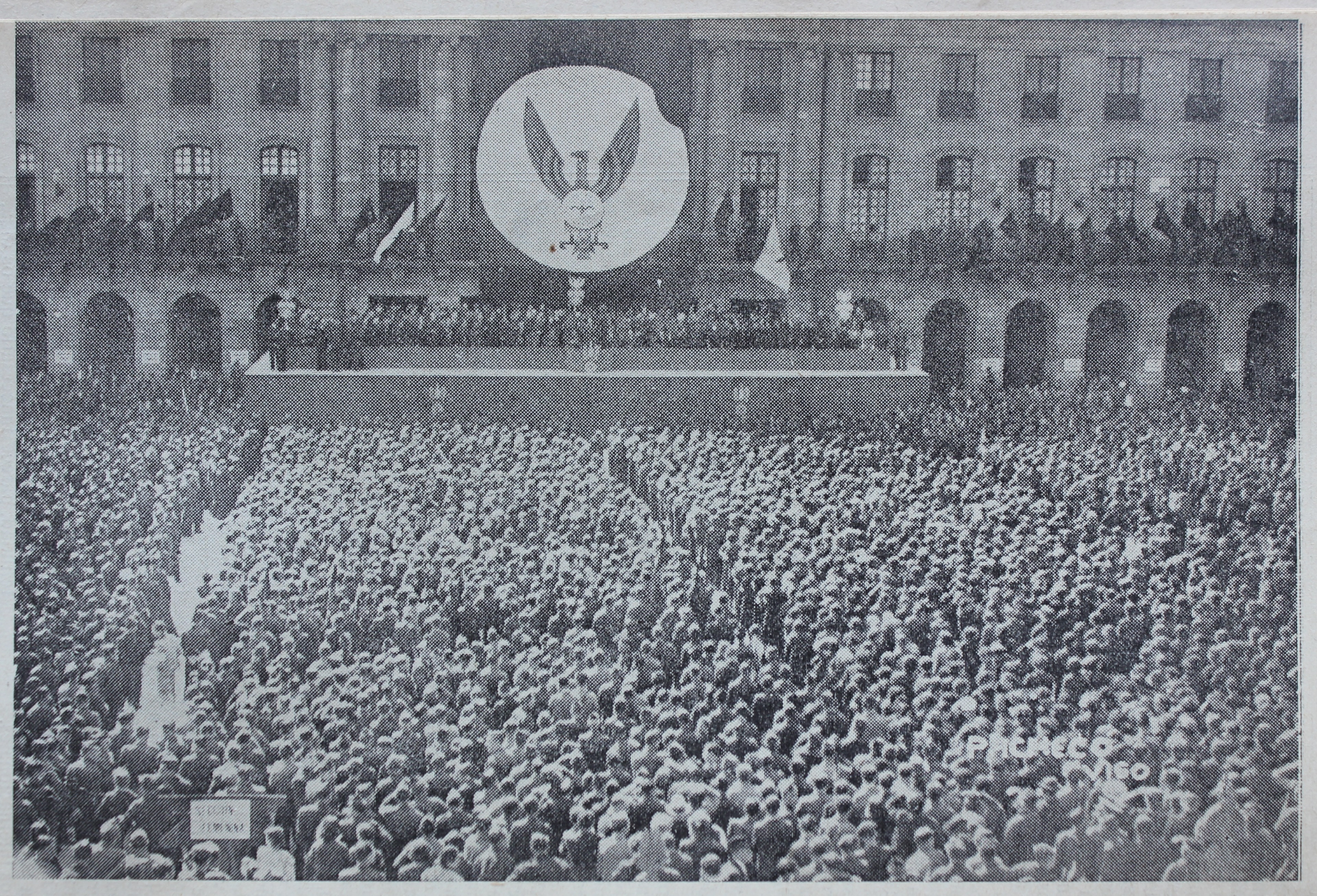

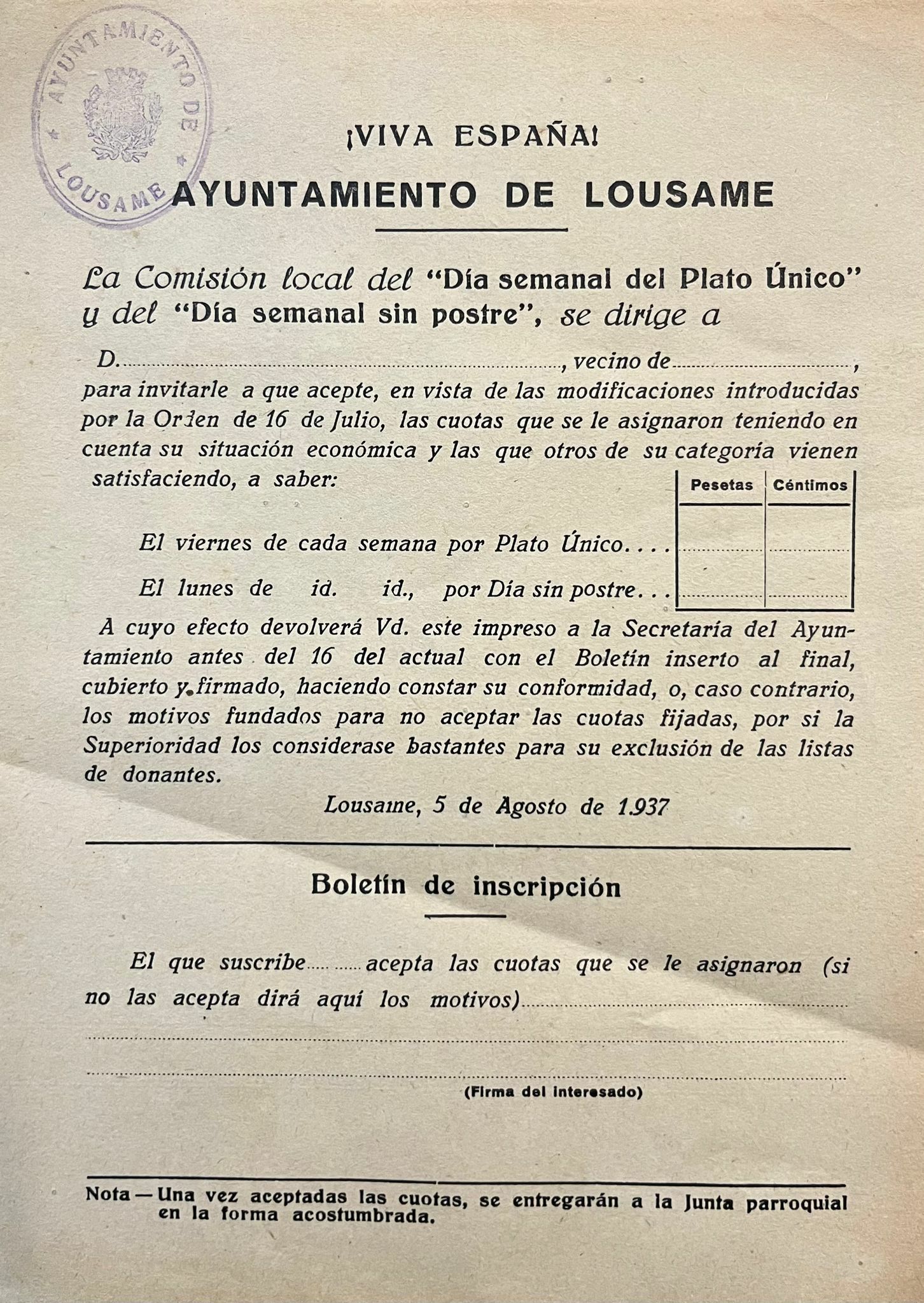

For most people, the coup came as a complete surprise, and in Galicia it was extremely violent. The assault on power came from a minority of military conspirators and an even smaller minority of civilian supporters without any meaningful political weight. Lacking social, economic or symbolic power, weapons were their only argument. With the senior commanders in the region having nothing to do with the conspiracy, the barracks themselves became a site of combat. Legality had to be eliminated through extreme violence. The centers of civil power, like the Civil Government building in A Coruña were bombarded, popular demonstrations met with massacres as in Vigo’s Puerta del Sol or the streets of Ferrol, and towns like Ribadeo and Tui that resisted occupied by columns of well-armed soldiers.

The balance sheet of what came next was inconceivable. The senior military commanders, the civil governors of the four provinces, dozens of mayors, including those of the seven big cities, hundreds of people holding positions in unions or political parties, socially important people like teachers, doctors and lawyers, as well as workers, sailors and peasants were murdered. By the end of the war, the total had reached five thousand.

This exterminating violence was organized hierarchically from the top down, but it was carried out from the bottom up by a variety of people. It was the military authorities who authorized and ordered practices that followed two parallel and complementary tracks: on the one hand, the thousands of sentences passed down by military courts; on the other, the “paseos”, or “rides”.

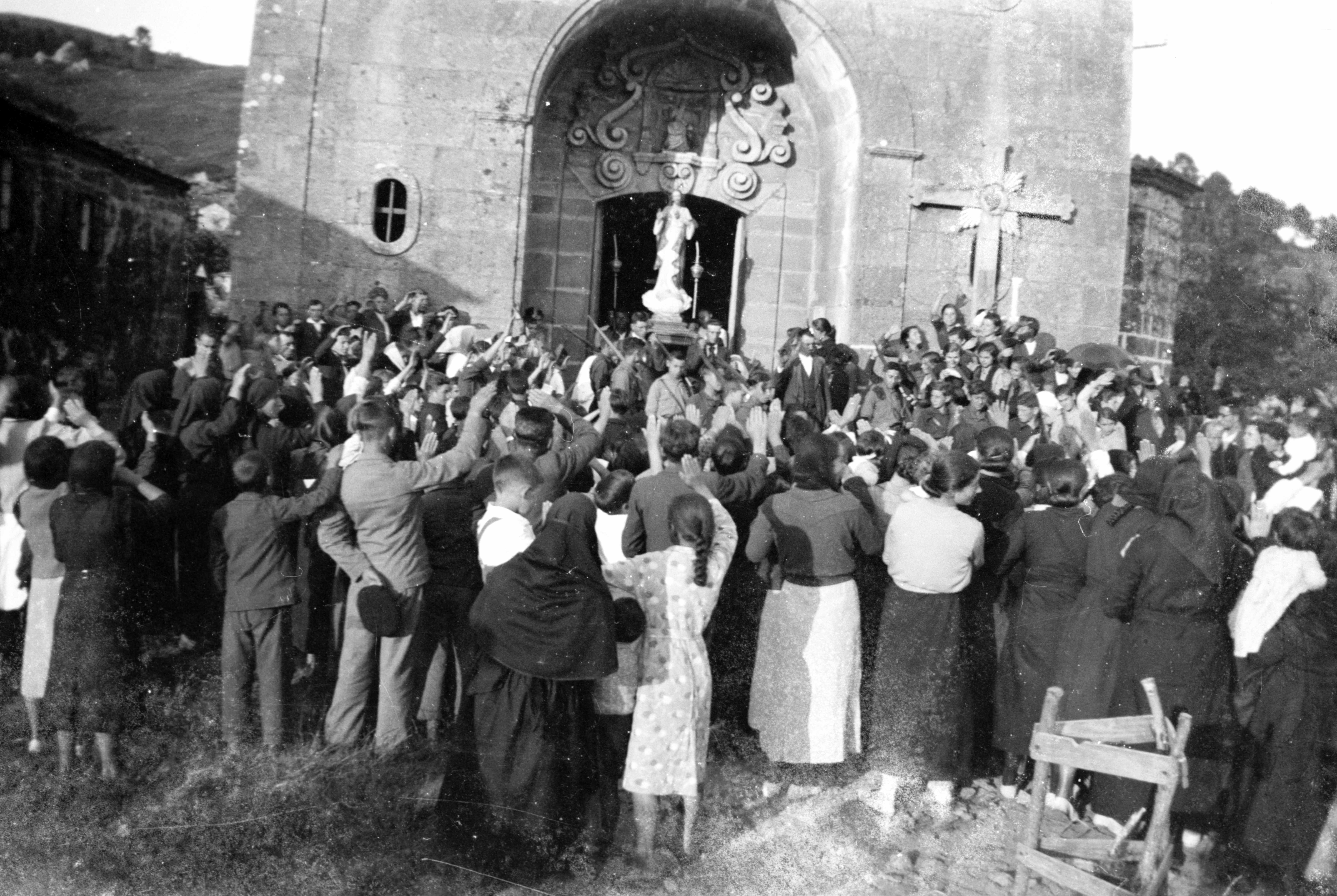

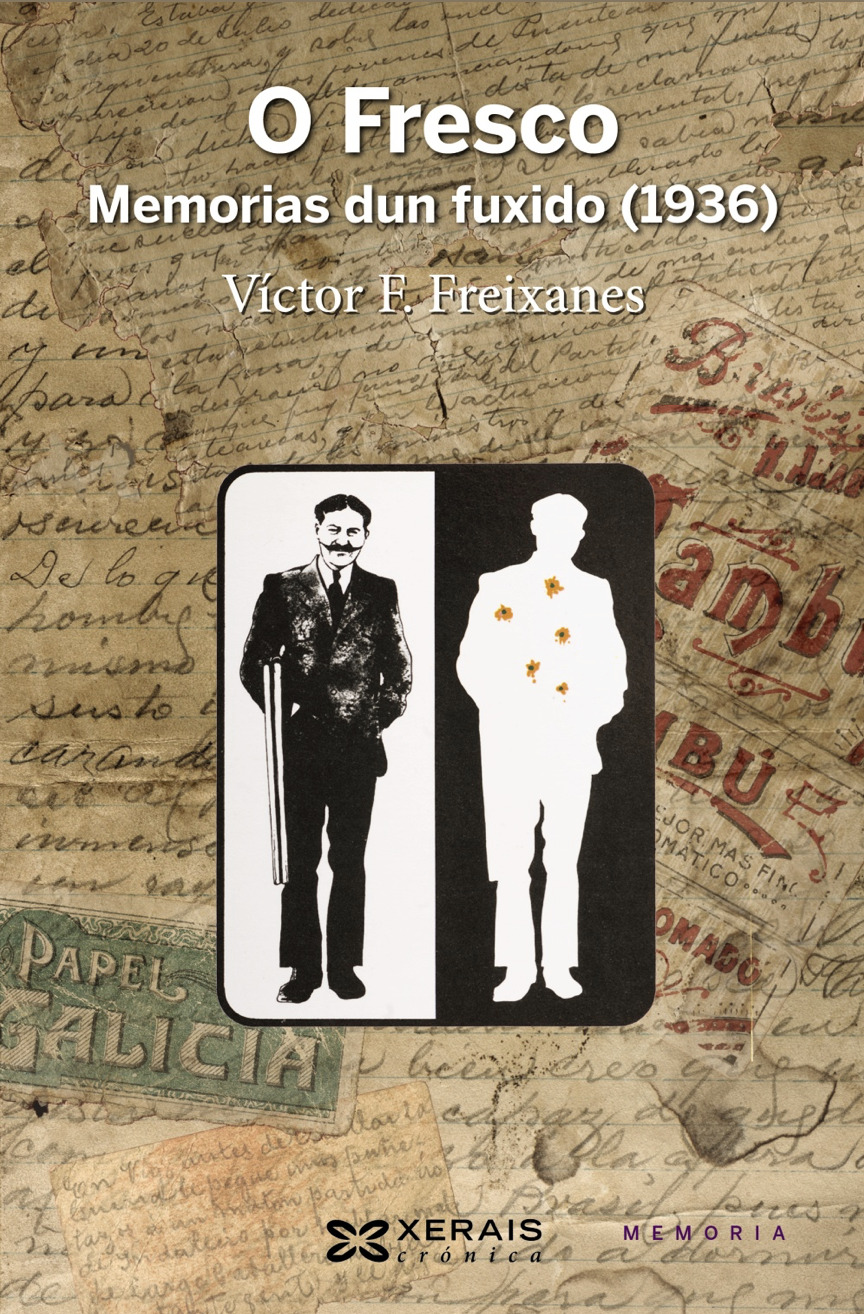

The memory of the coup and the war are very much alive in Galicia in the multiple public acts of homage to the victims that take place each year at the end of summer and in the fall. It is also present in the places of memory with monoliths, placques , and all kinds of signs that invoke the memory of the people who were murdered; in the flowers placed on their graves, both on land and in the fjords; and espcially in the speeches and the voices that, seized by the rebels’ narrative, feel the need to continue making the disconcerting argument: “they did nothing”. To which historians respond: “not them, but they who killed them did”.

AMM