U.S. colonial policies in Puerto Rico during the early decades of the 20th century opened the door to American sugar and tobacco plantation owners who seized control of agricultural land, enriching themselves while Puerto Ricans grew poorer. The widespread poverty led a significant portion of the population to emigrate, fleeing hunger and seeking a better life.

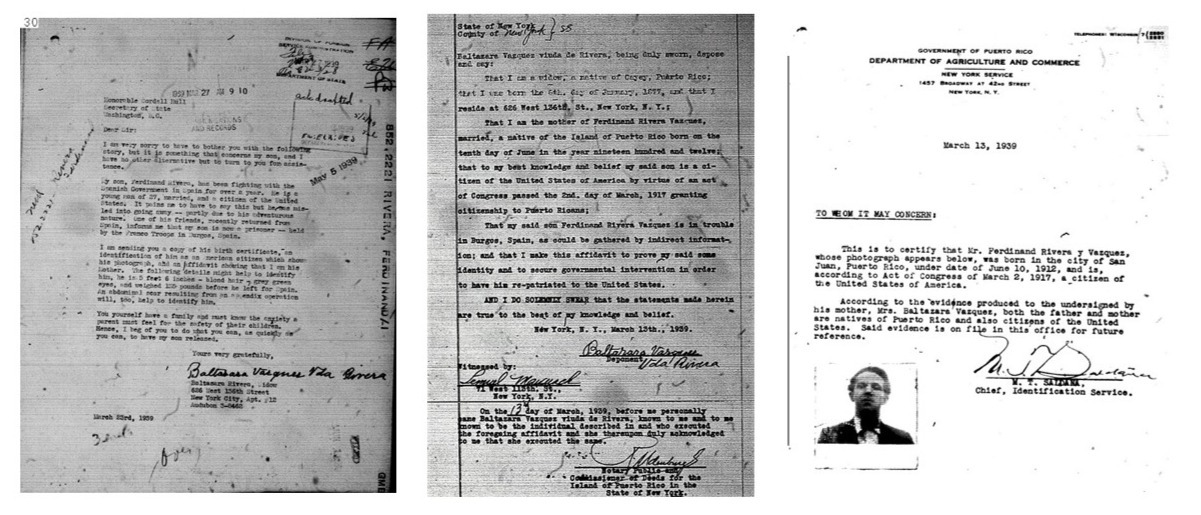

The first waves of migration (1900–1914) to Hawaii, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Ecuador, Colombia, and Mexico were promoted by the colonial authorities as a safety valve to manage Puerto Rico’s alleged overpopulation. The demand for food and manufactured goods during the Great War (1914–1918) triggered another wave of emigrants, this time to plantations in the southern United States and to the needlework and tobacco manufacturing centers in New York and New Jersey. The U.S. granted citizenship to those born in Puerto Rico during World War I (1917), which further encouraged and increased emigration, primarily to New York City.

When news of the uprising by a group of Spanish army officers against the legitimate government of the Spanish Republic began to make headlines in the country’s newspapers, Puerto Rico was in the midst of multiple strikes. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1934–1945) responded by appointing U.S. military officers to the colonial government to impose order and put an end to political, labor, and anti-colonial struggles.

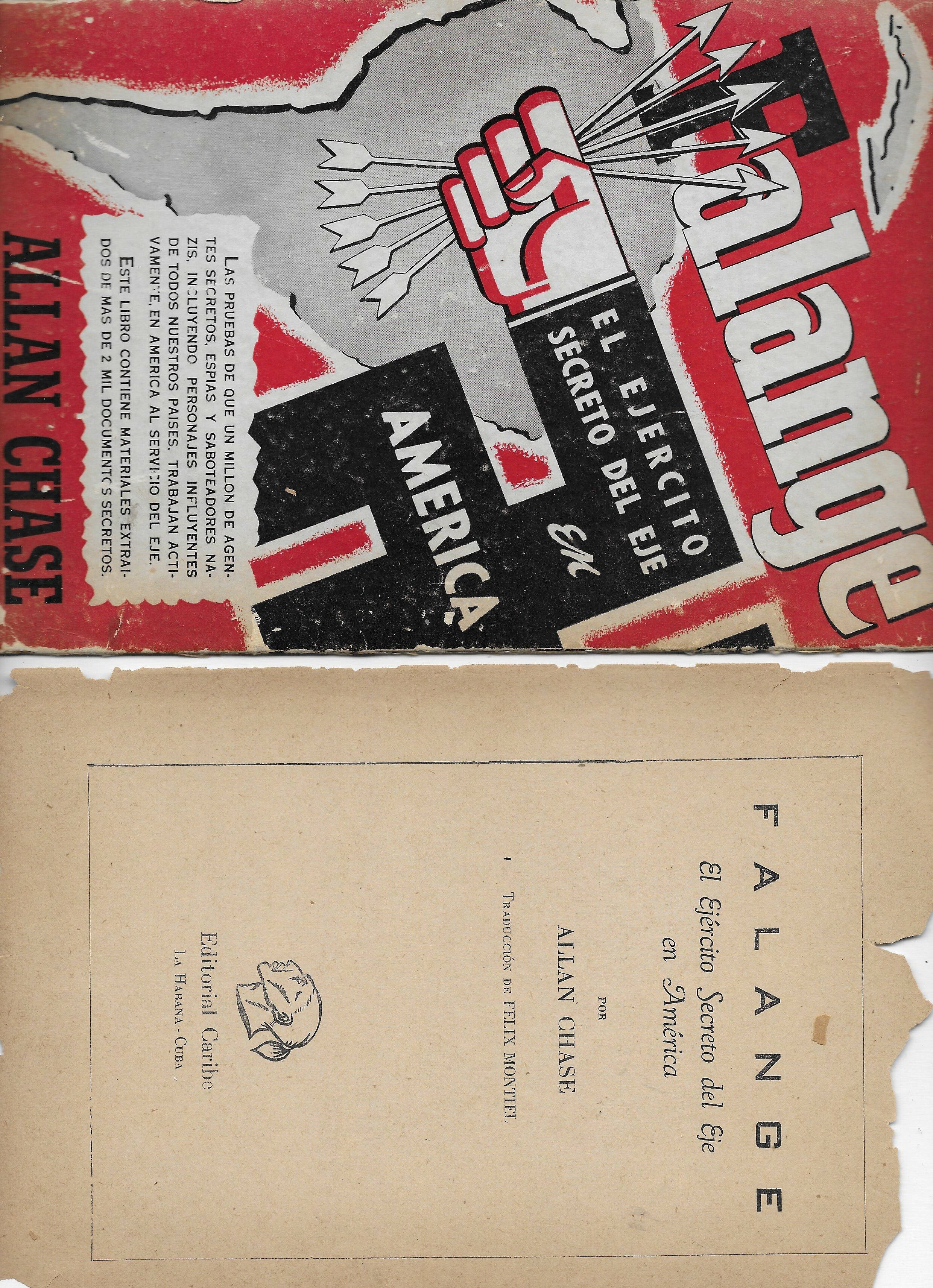

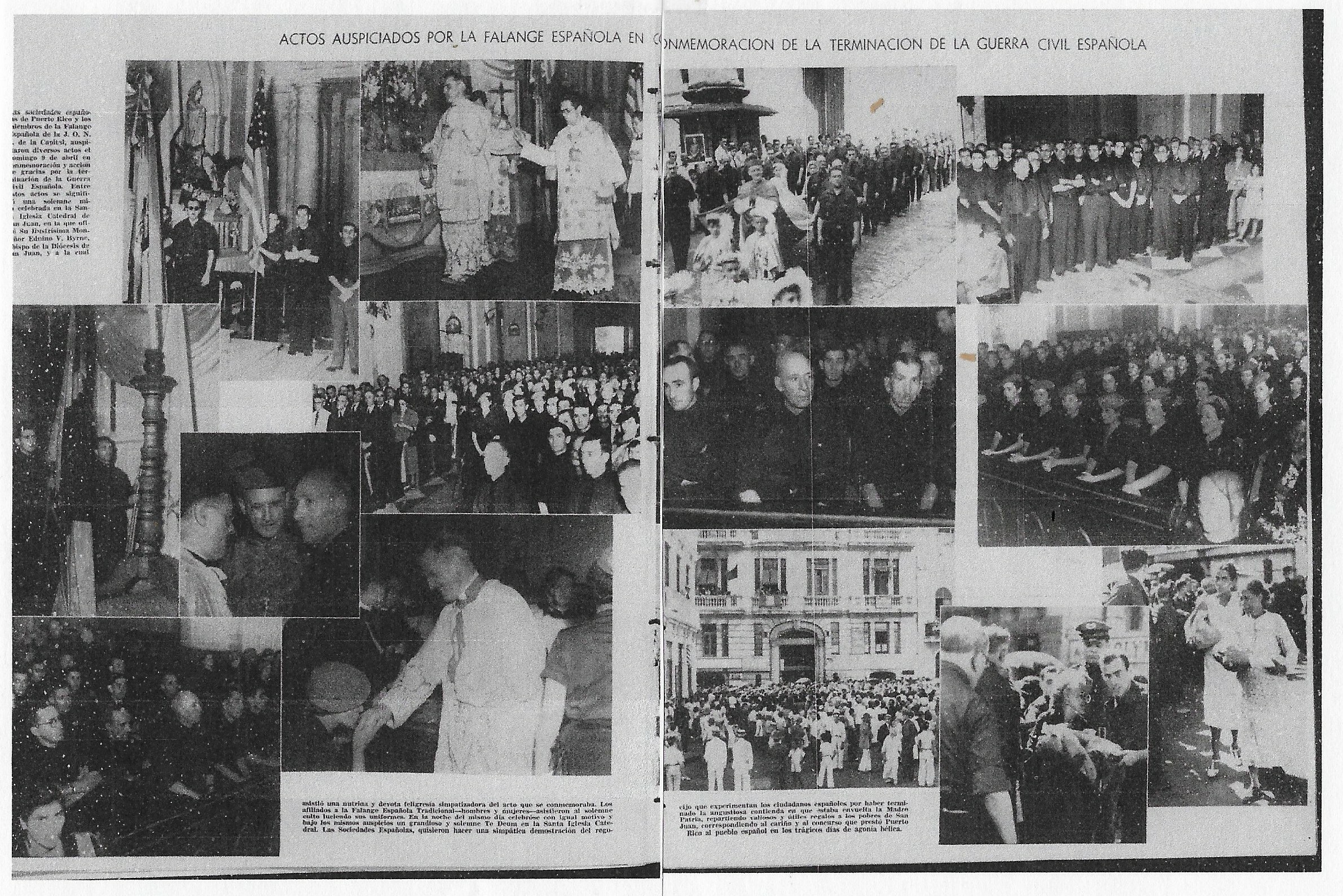

The politically conservative, monarchist, and economically powerful Spanish colony in Puerto Rico provided financial support to the military uprising and its leader, General Francisco Franco Bahamonde, and led a powerful propaganda campaign through newspapers, magazines, and radio. The Catholic Church, most of whose clergy were Spanish, also supported the uprising, viewing it as a crusade against the communist “reds” who sought to destroy the Church.

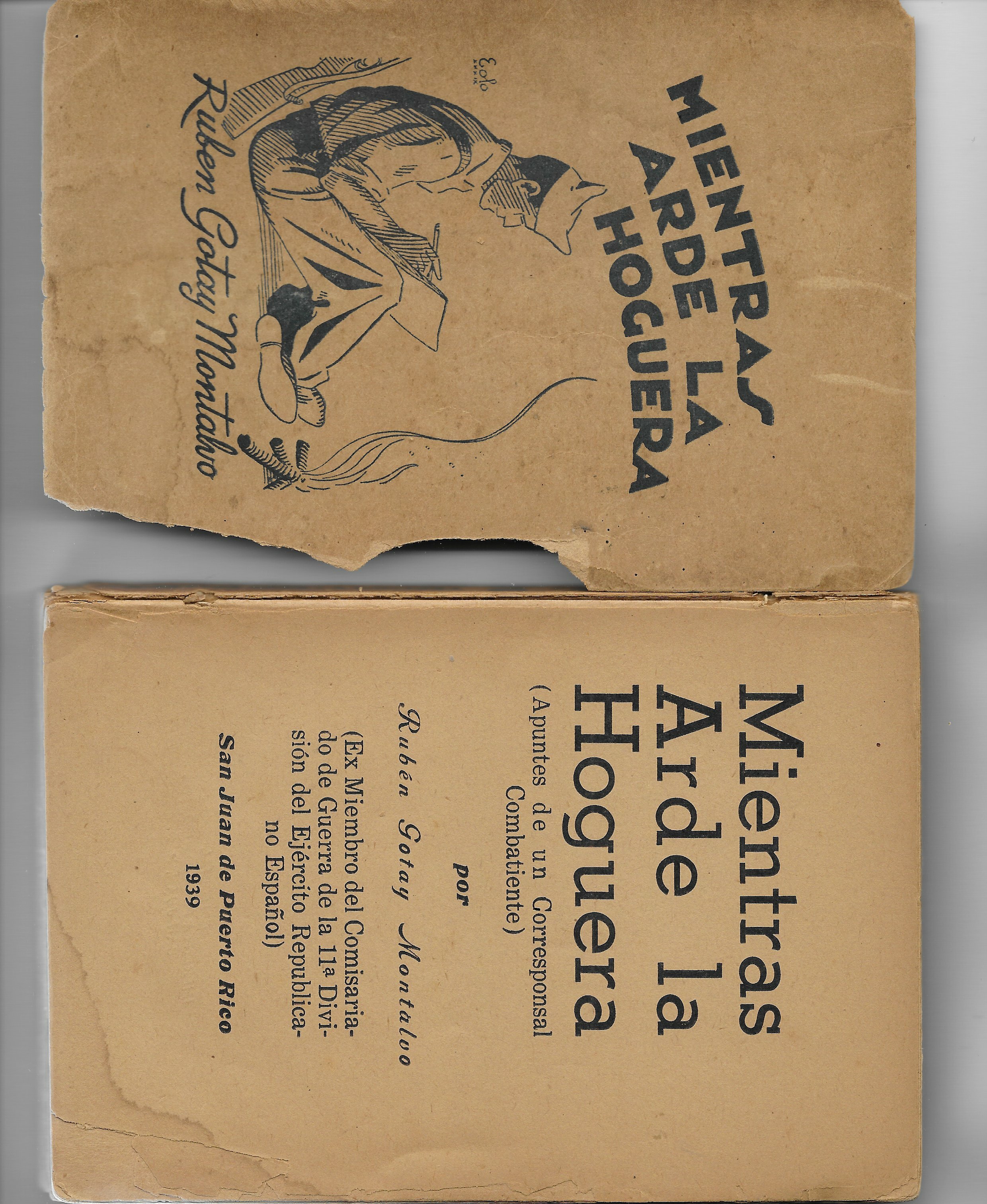

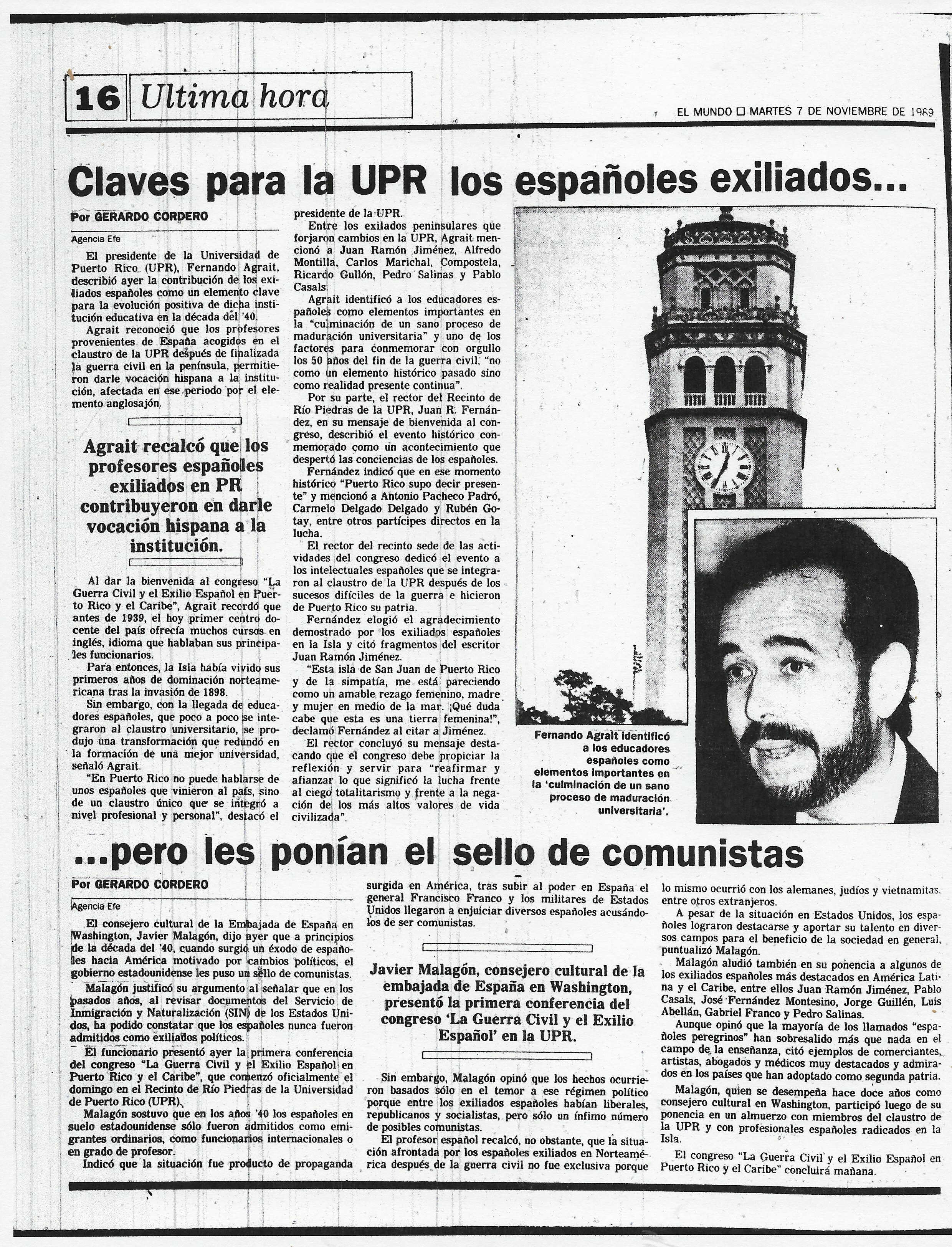

On the other hand, political parties, labor unions, university professors, cultural groups, students, and many Spaniards supported the Republic. Although they lacked financial backing, they had enough human resources to carry out propaganda activities in support of Spain’s legitimate government, organizing rallies, lectures, cultural events, and disseminating propaganda through newspapers and radio.

JAOC