The Spanish Civil War came hard on the heels of the world economic depression. In1934, almost a quarter of the Australian workforce was still unemployed. As in many other places, the Depression had polarized Australian political society. For almost a decade, Australian governments followed the lead of British conservatives to avoid the horrors of another Great War by eschewing all involvements which could upset the existing international balance of power. When the generals’ pronunciamiento took place in July 1936, the Prime Minister Joseph Lyons urged all Australians to stay out of the ‘folly’ of the Spanish civil war.

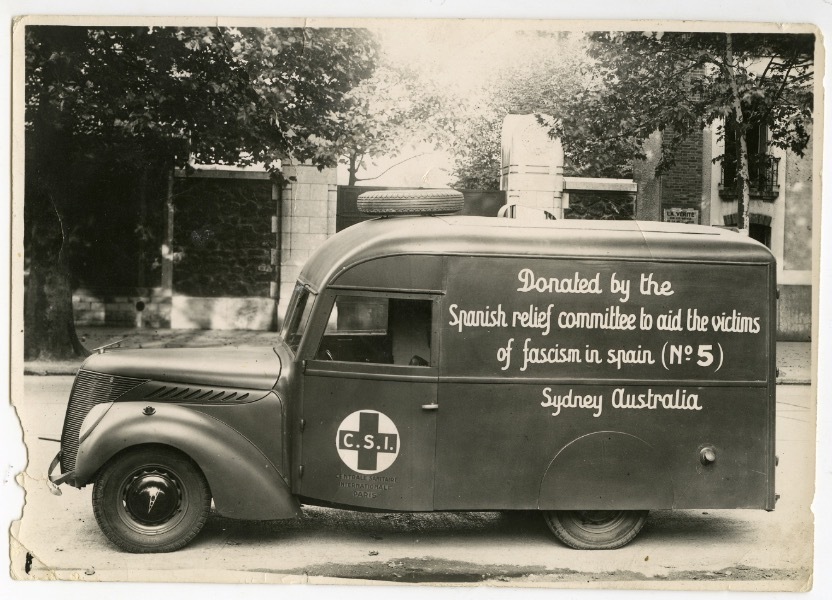

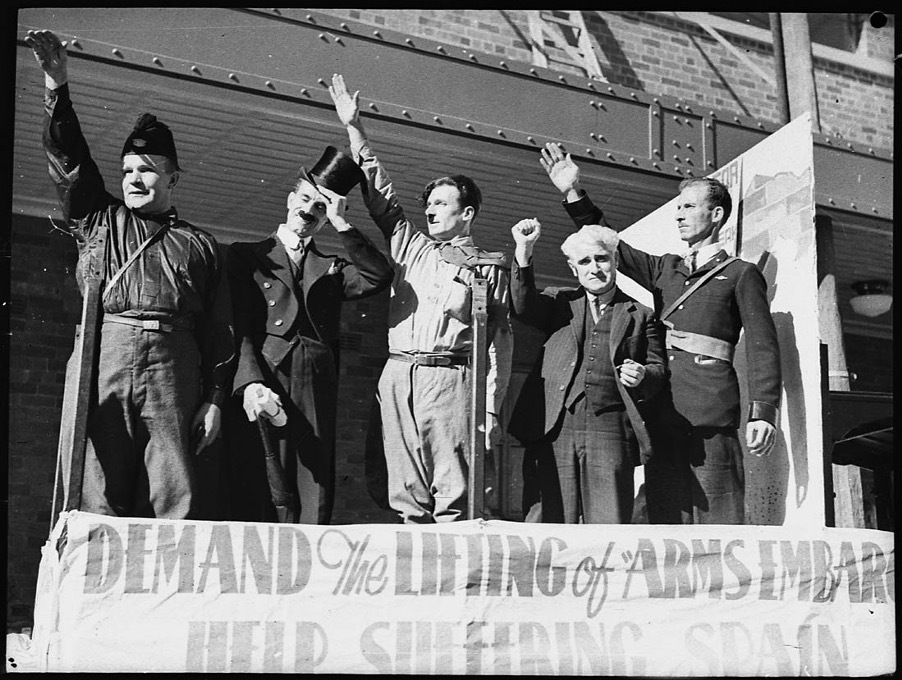

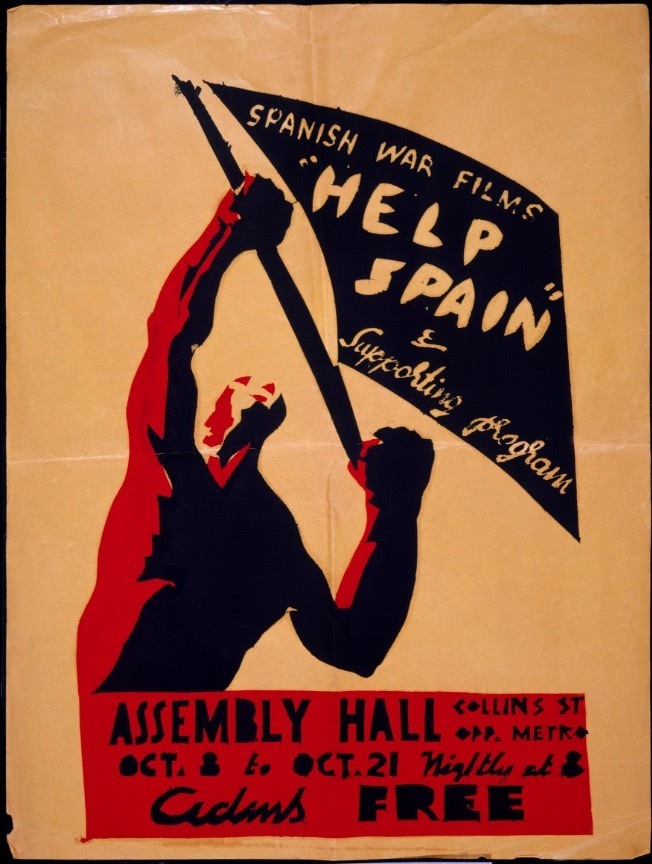

There were a number of Australian groups that were galvanised by the conflict in Spain. The Spanish Aid movement with the support of left-wing unions, the Australian Council of Trade Unions and several protestant church leaders raised public awareness about the threat to world peace by the increasing ebullience of European fascism. The Spanish Relief movement was formed in Sydney in August 1936. By mid 1937 there were groups in the large cities in all states as well as in remote mining areas and small settlements into the far north of Queensland.

The efforts of the Australian Spanish Aid campaigns were strongly countered by the Catholic church. Catholics comprised one fifth of the Australian population and while sectarianism and class were two deeply-entrenched sources of social division, trade union militancy and working class Catholicism, before the Spanish Civil War, were not antithetical. However, Spanish anti-clericalism was profoundly shocking to Australian Catholics, predominantly of Irish stock and among whom, since settlement, there had been strong bonds between hierarchy and laity in shared opposition to the hegemony of the British Anglican establishment. Since 1931, alarming reports syndicated from the Vatican press tracked the new Spanish Republic’s radical agenda for social reform with legalized divorce and illegitimate children accorded equal rights with those born in wedlock. In particular Spanish education reforms hit a raw nerve. While Australian Catholics were struggling to establish independent diocesan schooling, in Spain secular education had replaced the church’s traditional control of education.

Beginning in the Spanish Civil War there were increasing tensions between the Australian labour movement and Catholic trade unionists that eventually led to the formation of a separate Catholic labour party and separate trade union groupings.